7. Wealth Distribution Dynamics#

GPU

This lecture was built using a machine with access to a GPU — although it will also run without one.

Google Colab has a free tier with GPUs that you can access as follows:

Click on the “play” icon top right

Select Colab

Set the runtime environment to include a GPU

In this lecture we examine wealth dynamics in large cross-section of agents who are subject to both

idiosyncratic shocks, which affect labor income and returns, and

an aggregate shock, which also impacts on labor income and returns

In most macroeconomic models savings and consumption are determined by optimization.

Here savings and consumption behavior is taken as given – you can plug in your favorite model to obtain savings behavior and then analyze distribution dynamics using the techniques described below.

One of our interests will be how different aspects of wealth dynamics – such as labor income and the rate of return on investments – feed into measures of inequality, such as the Gini coefficient.

In addition to JAX and Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon

We will use the following imports:

import numba

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import quantecon as qe

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from time import time

Let’s check the GPU we are running

!nvidia-smi

Mon Jan 12 03:55:24 2026

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 580.105.08 Driver Version: 580.105.08 CUDA Version: 13.0 |

+-----------------------------------------+------------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M | Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap | Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

| | | MIG M. |

|=========================================+========================+======================|

| 0 Tesla T4 On | 00000000:00:1E.0 Off | 0 |

| N/A 28C P8 13W / 70W | 0MiB / 15360MiB | 0% Default |

| | | N/A |

+-----------------------------------------+------------------------+----------------------+

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: |

| GPU GI CI PID Type Process name GPU Memory |

| ID ID Usage |

|=========================================================================================|

| No running processes found |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

7.1. Wealth dynamics#

Wealth evolves as follows:

Here

\(w_t\) is wealth at time \(t\) for a given household,

\(r_t\) is the rate of return of financial assets,

\(y_t\) is labor income and

\(s(w_t)\) is savings (current wealth minus current consumption)

There is an aggregate state process

that affects the interest rate and labor income.

In particular, the gross interest rates obey

while

The tuple \(\{ (\epsilon_t, \xi_t, \zeta_t) \}\) is IID and standard normal in \(\mathbb R^3\).

(Each household receives their own idiosyncratic shocks.)

Regarding the savings function \(s\), our default model will be

where \(s_0\) is a positive constant.

Thus,

for \(w < \hat w\), the household saves nothing, while

for \(w \geq \bar w\), the household saves a fraction \(s_0\) of their wealth.

7.2. Implementation#

7.2.1. Numba implementation#

Here’s a function that collects parameters and useful constants

def create_wealth_model(w_hat=1.0, # Savings parameter

s_0=0.75, # Savings parameter

c_y=1.0, # Labor income parameter

μ_y=1.0, # Labor income parameter

σ_y=0.2, # Labor income parameter

c_r=0.05, # Rate of return parameter

μ_r=0.1, # Rate of return parameter

σ_r=0.5, # Rate of return parameter

a=0.5, # Aggregate shock parameter

b=0.0, # Aggregate shock parameter

σ_z=0.1): # Aggregate shock parameter

"""

Create a wealth model with given parameters.

Return a tuple model = (household_params, aggregate_params), where

household_params collects household information and aggregate_params

collects information relevant to the aggregate shock process.

"""

# Mean and variance of z process

z_mean = b / (1 - a)

z_var = σ_z**2 / (1 - a**2)

exp_z_mean = np.exp(z_mean + z_var / 2)

# Mean of R and y processes

R_mean = c_r * exp_z_mean + np.exp(μ_r + σ_r**2 / 2)

y_mean = c_y * exp_z_mean + np.exp(μ_y + σ_y**2 / 2)

# Test stability condition ensuring wealth does not diverge

# to infinity.

α = R_mean * s_0

if α >= 1:

raise ValueError("Stability condition failed.")

# Pack values into tuples and return them

household_params = (w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean)

aggregate_params = (a, b, σ_z, z_mean, z_var)

model = household_params, aggregate_params

return model

Here’s a function that generates the aggregate state process

@numba.jit

def generate_aggregate_state_sequence(aggregate_params, length=100):

a, b, σ_z, z_mean, z_var = aggregate_params

z = np.empty(length+1)

z[0] = z_mean # Initialize at z_mean

for t in range(length):

z[t+1] = a * z[t] + b + σ_z * np.random.randn()

return z

Here’s a function that updates household wealth by one period, taking the current value of the aggregate shock

@numba.jit

def update_wealth(household_params, w, z):

"""

Generate w_{t+1} given w_t and z_{t+1}.

"""

# Unpack

w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean = household_params

# Update wealth

y = c_y * np.exp(z) + np.exp(μ_y + σ_y * np.random.randn())

wp = y

if w >= w_hat:

R = c_r * np.exp(z) + np.exp(μ_r + σ_r * np.random.randn())

wp += R * s_0 * w

return wp

Here’s a function to simulate the time series of wealth for an individual household

@numba.jit

def wealth_time_series(model, w_0, sim_length):

"""

Generate a single time series of length sim_length for wealth given initial

value w_0. The function generates its own aggregate shock sequence.

"""

# Unpack

household_params, aggregate_params = model

a, b, σ_z, z_mean, z_var = aggregate_params

# Initialize and update

z = generate_aggregate_state_sequence(aggregate_params,

length=sim_length)

w = np.empty(sim_length)

w[0] = w_0

for t in range(sim_length-1):

w[t+1] = update_wealth(household_params, w[t], z[t+1])

return w

Let’s look at the wealth dynamics of an individual household

model = create_wealth_model()

household_params, aggregate_params = model

w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean = household_params

a, b, σ_z, z_mean, z_var = aggregate_params

ts_length = 200

w = wealth_time_series(model, y_mean, ts_length)

Notice the large spikes in wealth over time.

Such spikes are related to heavy tails in the wealth distribution, which we discuss below.

Here’s a function to simulate a cross section of households forward in time.

Note the use of parallelization to speed up computation.

@numba.jit(parallel=True)

def update_cross_section(model, w_distribution, z_sequence):

"""

Shifts a cross-section of households forward in time

Takes

* a current distribution of wealth values as w_distribution and

* an aggregate shock sequence z_sequence

and updates each w_t in w_distribution to w_{t+j}, where

j = len(z_sequence).

Returns the new distribution.

"""

# Unpack

household_params, aggregate_params = model

num_households = len(w_distribution)

new_distribution = np.empty_like(w_distribution)

z = z_sequence

# Update each household

for i in numba.prange(num_households):

w = w_distribution[i]

for t in range(sim_length):

w = update_wealth(household_params, w, z[t])

new_distribution[i] = w

return new_distribution

Parallelization works in the function above because the time path of each household can be calculated independently once the path for the aggregate state is known.

Let’s see how long it takes to shift a large cross-section of households forward 200 periods

sim_length = 200

num_households = 10_000_000

ψ_0 = np.full(num_households, y_mean) # Initial distribution

z_sequence = generate_aggregate_state_sequence(aggregate_params,

length=sim_length)

print("Generating cross-section using Numba")

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section(model, ψ_0, z_sequence)

numba_with_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {numba_with_compile} seconds.\n")

Generating cross-section using Numba

Generated cross-section in 27.439136266708374 seconds.

We run it again to eliminate compile time.

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section(model, ψ_0, z_sequence)

numba_without_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {numba_without_compile} seconds.\n")

Generated cross-section in 27.03705072402954 seconds.

7.2.2. JAX implementation#

Let’s redo some of the preceding calculations using JAX and see how execution speed compares

def update_cross_section_jax(model, w_distribution, z_sequence, key):

"""

Shifts a cross-section of households forward in time

Takes

* a current distribution of wealth values as w_distribution and

* an aggregate shock sequence z_sequence

and updates each w_t in w_distribution to w_{t+j}, where

j = len(z_sequence).

Returns the new distribution.

"""

# Unpack, simplify names

household_params, aggregate_params = model

w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean = household_params

w = w_distribution

n = len(w)

# Update wealth

for t, z in enumerate(z_sequence):

U = jax.random.normal(key, (2, n))

y = c_y * jnp.exp(z) + jnp.exp(μ_y + σ_y * U[0, :])

R = c_r * jnp.exp(z) + jnp.exp(μ_r + σ_r * U[1, :])

w = y + jnp.where(w < w_hat, 0.0, R * s_0 * w)

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

return w

Let’s see how long it takes to shift the cross-section of households forward using JAX

sim_length = 200

num_households = 10_000_000

ψ_0 = jnp.full(num_households, y_mean) # Initial distribution

z_sequence = generate_aggregate_state_sequence(aggregate_params,

length=sim_length)

z_sequence = jnp.array(z_sequence)

print("Generating cross-section using JAX")

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax(model, ψ_0, z_sequence, key).block_until_ready()

jax_with_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {jax_with_compile} seconds.\n")

Generating cross-section using JAX

Generated cross-section in 3.222991704940796 seconds.

print("Repeating without compile time.")

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax(model, ψ_0, z_sequence, key).block_until_ready()

jax_without_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {jax_without_compile} seconds")

Repeating without compile time.

Generated cross-section in 1.329458236694336 seconds

And let’s see how long it takes if we compile the loop.

def update_cross_section_jax_compiled(model,

w_distribution,

w_size,

z_sequence,

key):

"""

Shifts a cross-section of households forward in time

Takes

* a current distribution of wealth values as w_distribution and

* an aggregate shock sequence z_sequence

and updates each w_t in w_distribution to w_{t+j}, where

j = len(z_sequence).

Returns the new distribution.

"""

# Unpack, simplify names

household_params, aggregate_params = model

w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean = household_params

w = w_distribution

n = len(w)

z = z_sequence

sim_length = len(z)

def body_function(t, state):

key, w = state

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

U = jax.random.normal(subkey, (2, n))

y = c_y * jnp.exp(z[t]) + jnp.exp(μ_y + σ_y * U[0, :])

R = c_r * jnp.exp(z[t]) + jnp.exp(μ_r + σ_r * U[1, :])

w = y + jnp.where(w < w_hat, 0.0, R * s_0 * w)

return key, w

key, w = jax.lax.fori_loop(0, sim_length, body_function, (key, w))

return w

update_cross_section_jax_compiled = jax.jit(

update_cross_section_jax_compiled, static_argnums=(2,)

)

print("Generating cross-section using JAX with compiled loop")

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

).block_until_ready()

jax_fori_with_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {jax_fori_with_compile} seconds.\n")

Generating cross-section using JAX with compiled loop

Generated cross-section in 1.0351390838623047 seconds.

print("Repeating without compile time")

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

start = time()

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

).block_until_ready()

jax_fori_without_compile = time() - start

print(f"Generated cross-section in {jax_fori_without_compile} seconds")

Repeating without compile time

Generated cross-section in 0.16712331771850586 seconds

print(f"JAX is {numba_without_compile/jax_fori_without_compile:.4f} times faster.\n")

JAX is 161.7790 times faster.

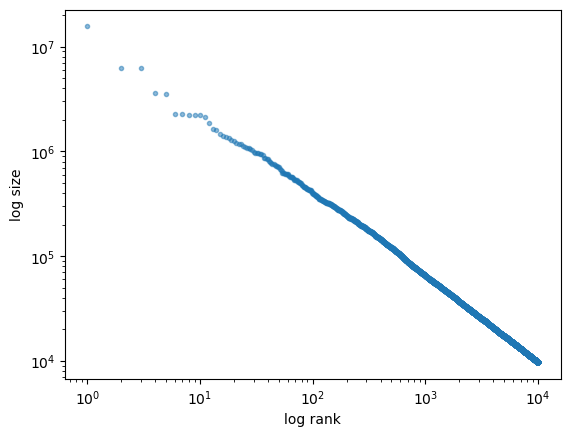

7.2.3. Pareto tails#

In most countries, the cross-sectional distribution of wealth exhibits a Pareto tail (power law).

Let’s see if our model can replicate this stylized fact by running a simulation that generates a cross-section of wealth and generating a suitable rank-size plot.

We will use the function rank_size from quantecon library.

In the limit, data that obeys a power law generates a straight line.

model = create_wealth_model()

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

rank_data, size_data = qe.rank_size(ψ_star, c=0.001)

ax.loglog(rank_data, size_data, 'o', markersize=3.0, alpha=0.5)

ax.set_xlabel("log rank")

ax.set_ylabel("log size")

plt.show()

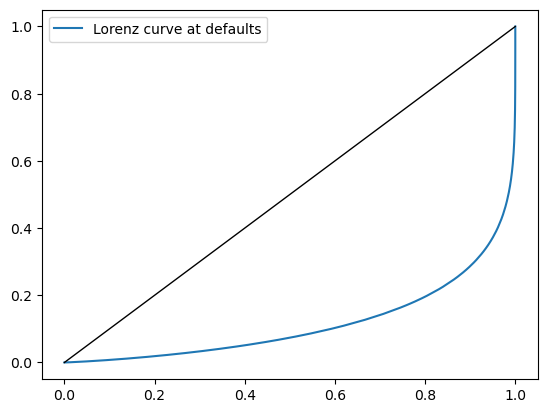

7.2.4. Lorenz curves and Gini coefficients#

To study the impact of parameters on inequality, we examine Lorenz curves and the Gini coefficients at different parameters.

QuantEcon provides functions to compute Lorenz curves and Gini coefficients that are accelerated using Numba.

Here we provide JAX-based functions that do the same job and are faster for large data sets on parallel hardware.

7.2.4.1. Lorenz curve#

Recall that, for sorted data \(w_1, \ldots, w_n\), the Lorenz curve generates data points \((x_i, y_i)_{i=0}^n\) according to

def _lorenz_curve_jax(w, w_size):

n = w.shape[0]

w = jnp.sort(w)

x = jnp.arange(n + 1) / n

s = jnp.concatenate((jnp.zeros(1), jnp.cumsum(w)))

y = s / s[n]

return x, y

lorenz_curve_jax = jax.jit(_lorenz_curve_jax, static_argnums=(1,))

Let’s test

sim_length = 200

num_households = 1_000_000

ψ_0 = jnp.full(num_households, y_mean) # Initial distribution

z_sequence = generate_aggregate_state_sequence(aggregate_params,

length=sim_length)

z_sequence = jnp.array(z_sequence)

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

%time _ = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

CPU times: user 243 ms, sys: 17 ms, total: 260 ms

Wall time: 296 ms

# Now time it without compile time

%time x, y = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

CPU times: user 673 μs, sys: 2 μs, total: 675 μs

Wall time: 348 μs

7.2.4.2. Gini Coefficient#

Recall that, for sorted data \(w_1, \ldots, w_n\), the Gini coefficient takes the form

Here’s a function that computes the Gini coefficient using vectorization.

def _gini_jax(w, w_size):

w_1 = jnp.reshape(w, (w_size, 1))

w_2 = jnp.reshape(w, (1, w_size))

g_sum = jnp.sum(jnp.abs(w_1 - w_2))

return g_sum / (2 * w_size * jnp.sum(w))

gini_jax = jax.jit(_gini_jax, static_argnums=(1,))

%time gini = gini_jax(ψ_star, num_households).block_until_ready()

CPU times: user 273 ms, sys: 7 ms, total: 280 ms

Wall time: 7.14 s

# Now time it without compilation

%time gini = gini_jax(ψ_star, num_households).block_until_ready()

CPU times: user 2.66 ms, sys: 2.01 ms, total: 4.67 ms

Wall time: 6.61 s

gini

Array(0.7685361, dtype=float32)

7.3. Exercises#

Exercise 7.1

In this exercise, write an alternative version of gini_jax that uses vmap instead of reshaping and broadcasting.

Test with the same array to see if you can obtain the same output

Solution

Here’s one solution:

@jax.jit

def gini_jax_vmap(w):

def _inner_sum(x):

return jnp.sum(jnp.abs(x - w))

inner_sum = jax.vmap(_inner_sum)

full_sum = jnp.sum(inner_sum(w))

return full_sum / (2 * len(w) * jnp.sum(w))

%time gini = gini_jax_vmap(ψ_star).block_until_ready()

CPU times: user 132 ms, sys: 7.98 ms, total: 140 ms

Wall time: 6.78 s

# Now time it without compile time

%time gini = gini_jax_vmap(ψ_star).block_until_ready()

CPU times: user 4.48 ms, sys: 17 μs, total: 4.5 ms

Wall time: 6.61 s

gini

Array(0.7685361, dtype=float32)

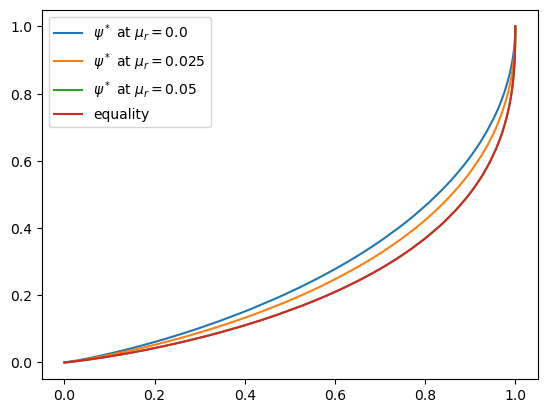

Exercise 7.2

In this exercise we investigate how the parameters determining the rate of return on assets and labor income shape inequality.

In doing so we recall that

while

Investigate how the Lorenz curves and the Gini coefficient associated with the wealth distribution change as return to savings varies.

In particular, plot Lorenz curves for the following three different values of \(\mu_r\)

μ_r_vals = (0.0, 0.025, 0.05)

Use the following as your initial cross-sectional distribution

num_households = 1_000_000

ψ_0 = jnp.full(num_households, y_mean) # Initial distribution

Once you have done that, plot the Gini coefficients as well.

Do the outcomes match your intuition?

Solution

Here is one solution

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

gini_vals = []

for μ_r in μ_r_vals:

model = create_wealth_model(μ_r=μ_r)

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

x, y = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

g = gini_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

ax.plot(x, y, label=f'$\psi^*$ at $\mu_r = {μ_r:0.2}$')

gini_vals.append(g)

ax.plot(x, y, label='equality')

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.show()

The Lorenz curve shifts downwards as returns on financial income rise, indicating a rise in inequality.

Now let’s check the Gini coefficient

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(μ_r_vals, gini_vals, label='Gini coefficient')

ax.set_xlabel("$\mu_r$")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

As expected, inequality increases as returns on financial income rise.

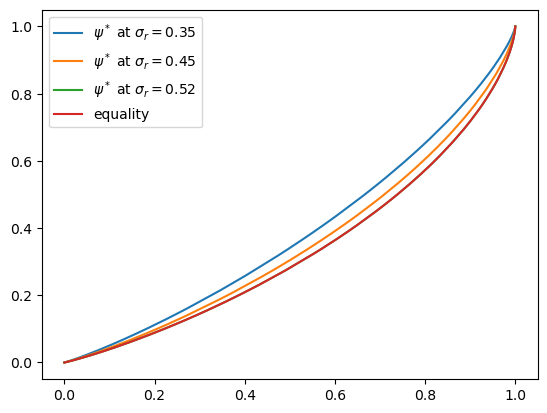

Exercise 7.3

Now investigate what happens when we change the volatility term \(\sigma_r\) in financial returns.

Use the same initial condition as before and the sequence

σ_r_vals = (0.35, 0.45, 0.52)

To isolate the role of volatility, set \(\mu_r = - \sigma_r^2 / 2\) at each \(\sigma_r\).

(This holds the variance of the idiosyncratic term \(\exp(\mu_r + \sigma_r \zeta)\) constant.)

Solution

Here’s one solution

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(1234)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

gini_vals = []

for σ_r in σ_r_vals:

model = create_wealth_model(σ_r=σ_r, μ_r=(-σ_r**2/2))

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

x, y = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

g = gini_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

ax.plot(x, y, label=f'$\psi^*$ at $\sigma_r = {σ_r:0.2}$')

gini_vals.append(g)

ax.plot(x, y, label='equality')

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.show()

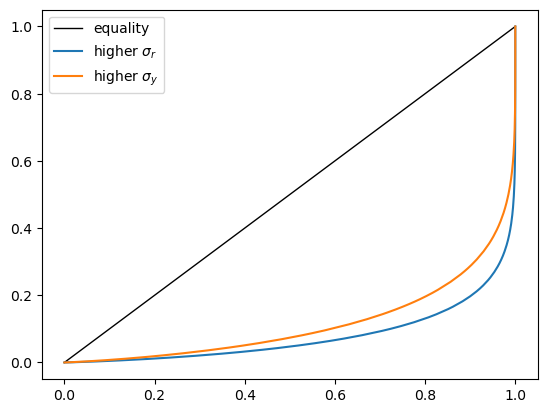

Exercise 7.4

In this exercise, examine which has more impact on inequality:

a 5% rise in volatility of the rate of return,

or a 5% rise in volatility of labor income.

Test this by

Shifting \(\sigma_r\) up 5% from the baseline and plotting the Lorenz curve

Shifting \(\sigma_y\) up 5% from the baseline and plotting the Lorenz curve

Plot both on the same figure and examine the result.

Solution

Here’s one solution.

It shows that increasing volatility in financial income has a greater effect

model = create_wealth_model()

household_params, aggregate_params = model

w_hat, s_0, c_y, μ_y, σ_y, c_r, μ_r, σ_r, y_mean = household_params

σ_r_default = σ_r

σ_y_default = σ_y

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

x_default, y_default = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

model = create_wealth_model(σ_r=(1.05 * σ_r_default))

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

x_financial, y_financial = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

model = create_wealth_model(σ_y=(1.05 * σ_y_default))

ψ_star = update_cross_section_jax_compiled(

model, ψ_0, num_households, z_sequence, key

)

x_labor, y_labor = lorenz_curve_jax(ψ_star, num_households)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(x_default, x_default, 'k-', lw=1, label='equality')

ax.plot(x_financial, y_financial, label=r'higher $\sigma_r$')

ax.plot(x_labor, y_labor, label=r'higher $\sigma_y$')

ax.legend()

plt.show()